An exhibition at Tate Liverpool, looking at landscape from the early twentieth century onwards in relation to history, identity and dissent. It didn’t really sound like my kind of thing and on entering I was immediately put off – as I am more and more these days – by the competing soundscapes that greeted me. John Berger (always worth listening to) on a loop competed with a dreary reciting voice, a bank of TV screens (like a cut-price Radio Rentals) and a 1950 MAFF information film advising farmers what to do in the event of a nuclear attack.

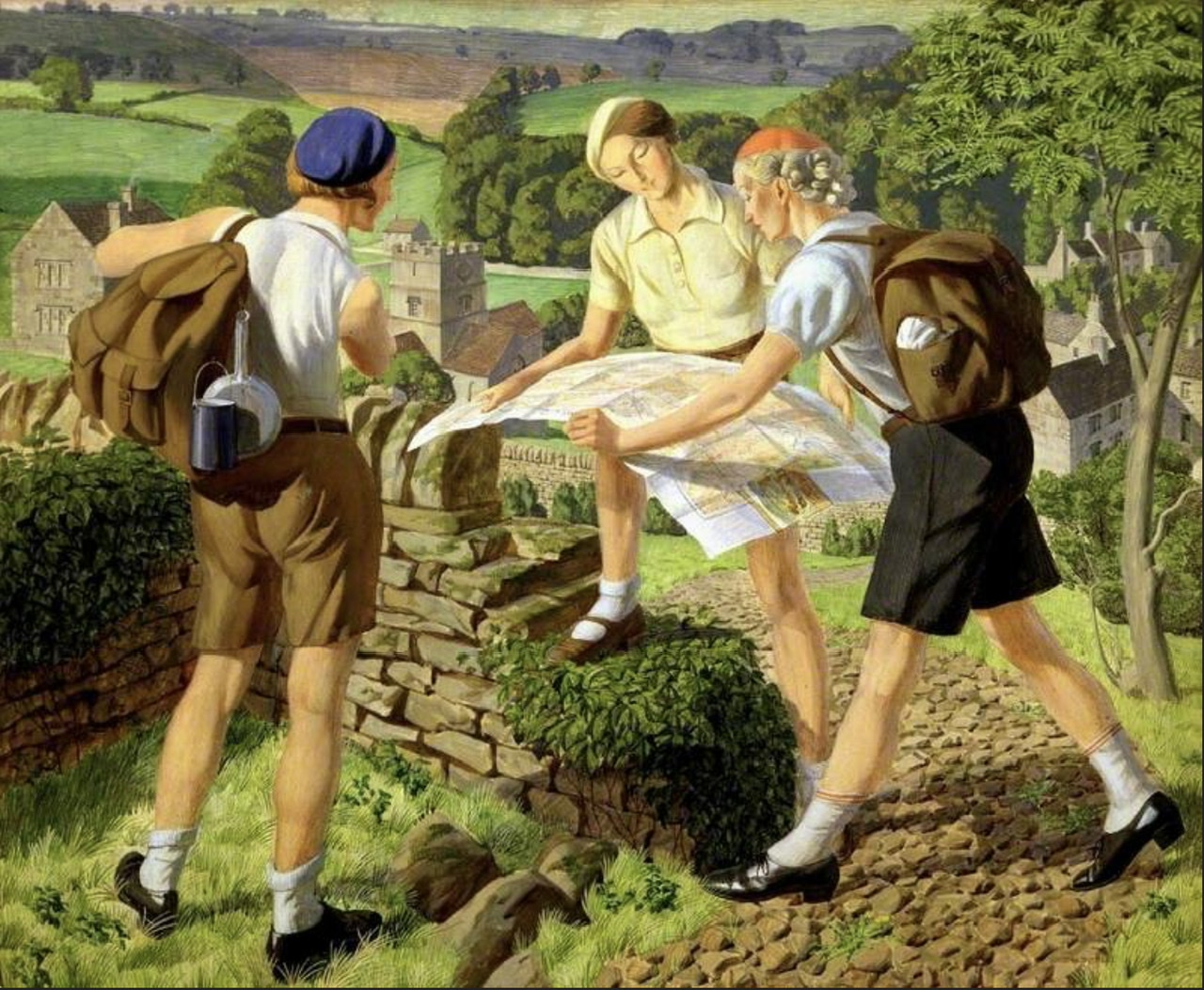

I found the exhibition incoherent but occasionally stimulating. The poor British landscape! It seemed on this reading to exist to promote wellbeing and validate identity, host raves, provide a living, represent an Earth Mother and inspire acts of creativity. Can it bear the weight of all these expectations? There was plenty about land ownership (Berger is brilliant on that) and resistance to it, but nothing about non-anthropocentric nature or beauty. There was an air of disappointment that Constable’s Flatford Mill said nothing about the enclosures, which is . . . OK, whatevs. But to say that it depicts the countryside as a place of leisure when a boy is clearly leading the horse towing the boat is off beam. He’s not doing dressage: he’s working.

Yes, of course my attention was caught by some exhibits. Tacita Dean’s oak, Eric Ravilious, John Nash, the discovery of the odd-sounding Kibbo Kift, and even, momentarily, Ruth Ewan’s ”Back to the Fields”. This was a representation of the French Republican calendar, with its ten-day weeks et al. I was ready to yawn but didn’t. The installation itself – 360 agricultural objects representing a rural alternative to the saints calendar (a day for barley rather than St Barnabas) – was underwhelming until I focussed on two or three objects, moved away from the visual, and thought about the aims behind the restructuring of the calendar: a desire to sweep away all religious references, to rationalise the way time is counted, to focus on the essential rural labour that feeds us all. The fact that the installation had been plagued with fruit flies was ironic: art having no idea of the messier side of nature.

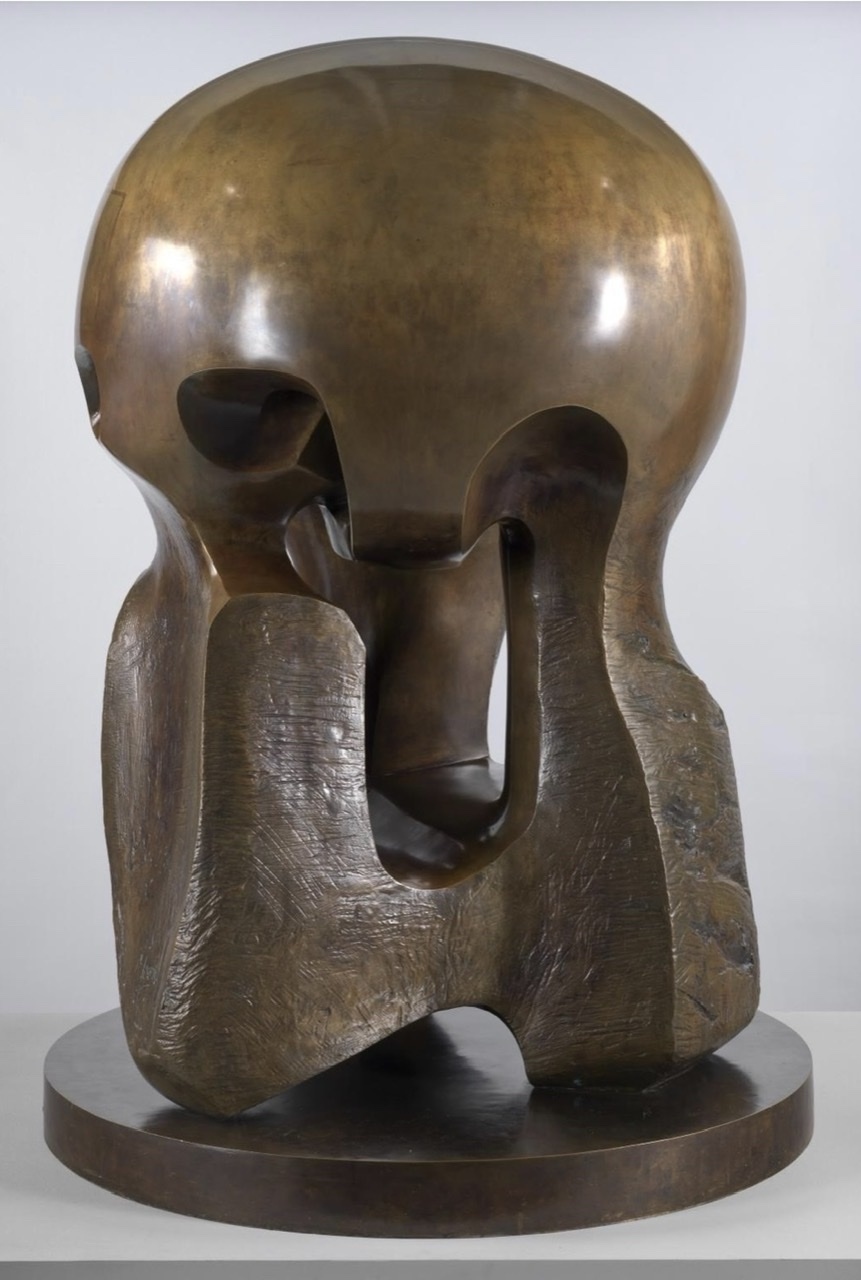

Moore’s sculpture invited touch (I didn’t) and sent me thinking about mushroom clouds and brains (the Mekon) and war (a Spartan helmet).

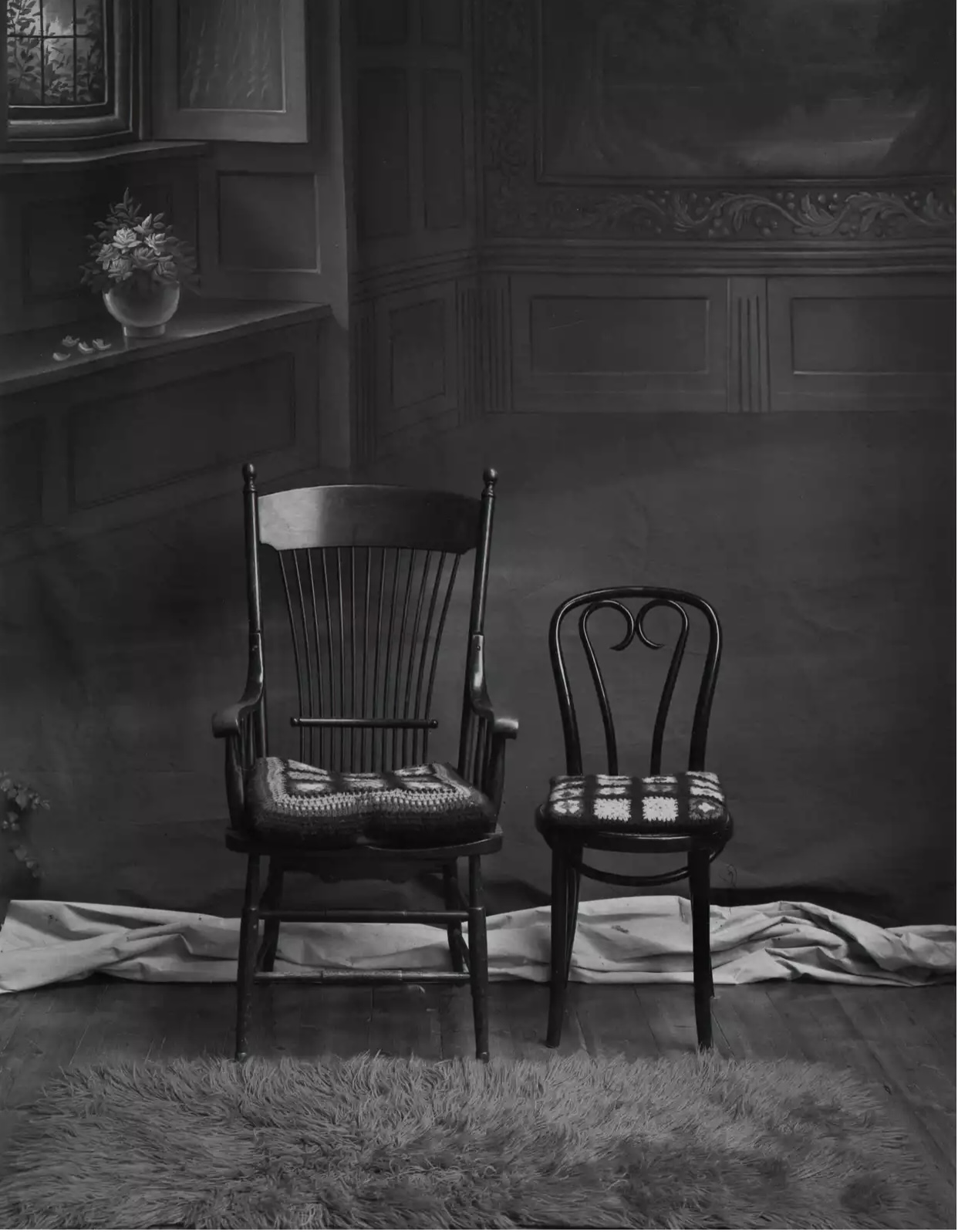

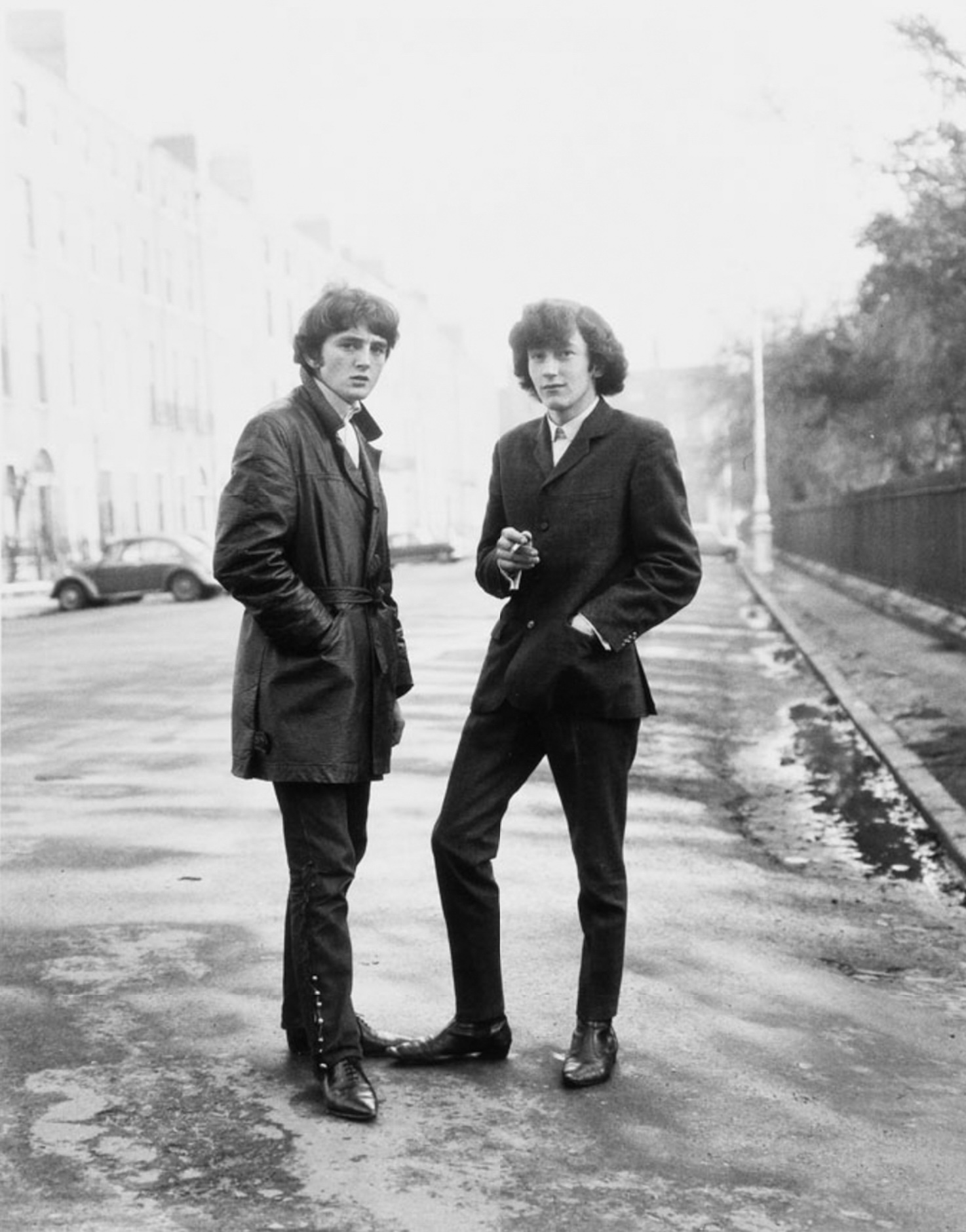

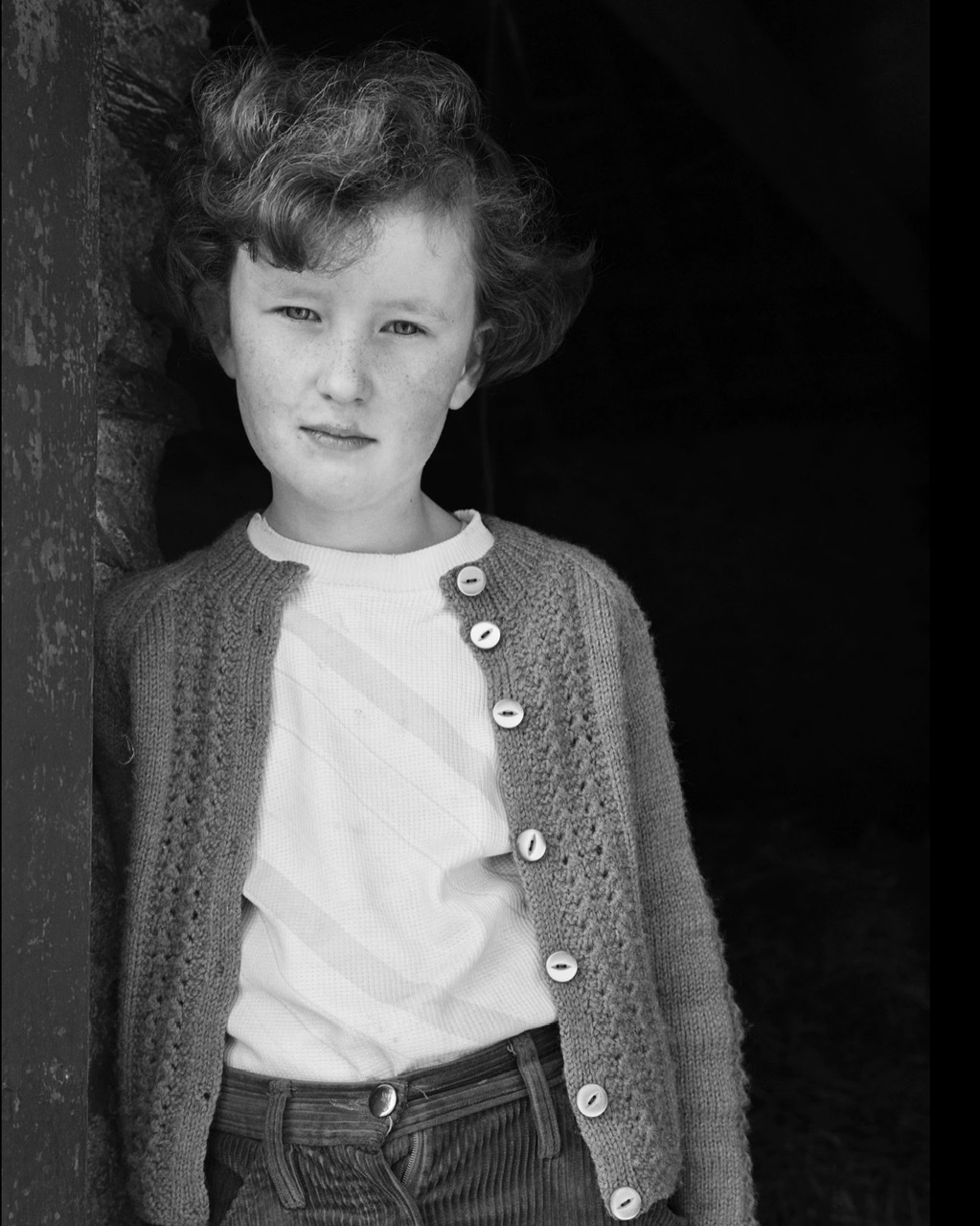

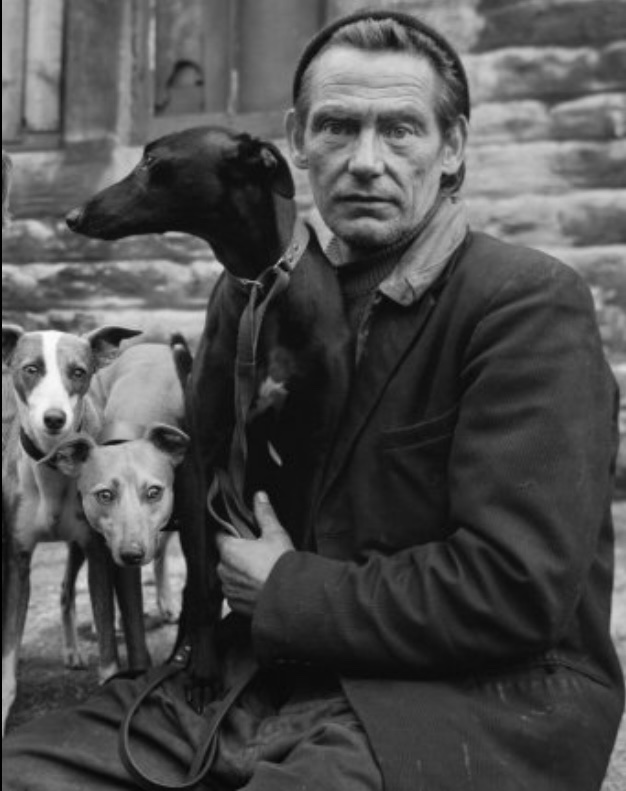

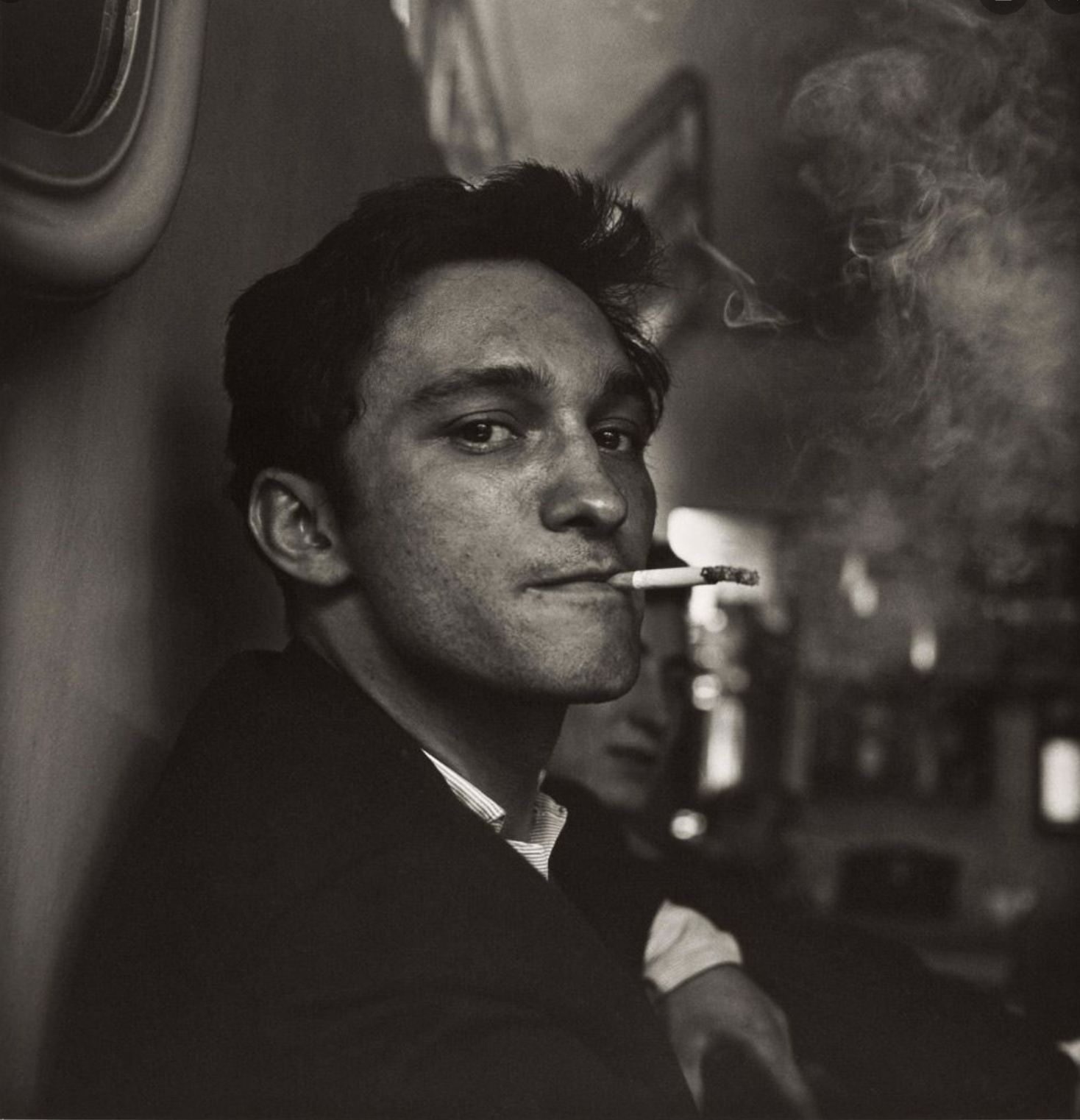

What remains, however, are Chris Killip’s black-and-white photographs of seacoal gleaners in Northumberland. Magnificent and bleak, they captured perfectly what the rest of the exhibits had overlooked: the rawness of the natural world and how being a part of it is discomforting as well as elemental.