I had been bitten by the Victorian bug after yesterday’s visit to the V&A – and I also had a hankering to take another look at the old Derry & Toms building. So off I went.

There are actually two art deco former department stores side by side, both once owned by the same company and both designed by Bernard George in the 1930s. The one with the giant fins was Barkers of Kensington; it wasn’t actually finished until the 1950s. Of the two, I prefer Derry & Toms: the detailing is wonderful. I delighted in the decorated lintels above the entrances: the bizarre inclusion of squirrels and kingfishers in this most urban of places. The panel reliefs of transport, cosmetics and labour are more appropriate – but less cute. Having said that, there was/is also a roof garden – so the natural world is not entirely absent.

And now these two buildings have lost much of their function. Derry & Toms gave way to Biba (now that’s an experience I regret missing); there are still shops inside but they are dwarfed by their surroundings.

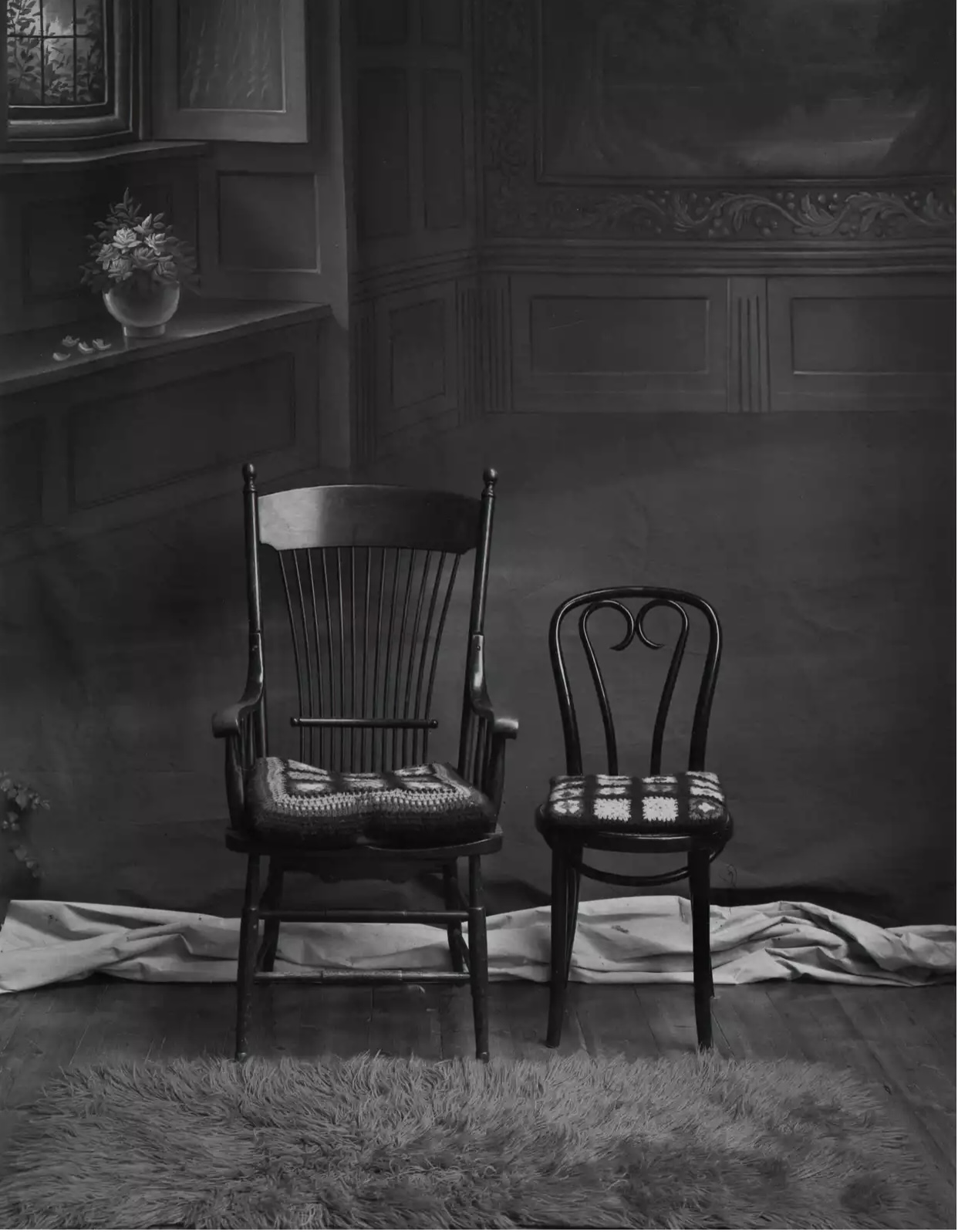

From the twentieth century to the nineteenth: I visited Sambourne House, the home of Linley Sambourne (1844-1910) and his family. He was an illustrator and cartoonist, mainly for Punch, and the house is furnished in the “aesthetic” style of the time – but with added clutter. So lots of Morris wallpaper; flowers and birds everywhere on carpets, door panels, stained glass; walls divided into three by dado rails and picture rails and then covered in wallpapers, prints, paintings and reproductions. It was exhausting! There were also lots of “Arnolfini” mirrors – but not used as creatively as in Soane’s House. I was glad I had arrived early as I had the house to myself to wander around; the silence of the rooms countered the oppressive sense of “stuff” that was never far from the surface, despite my pleasure in looking round.

I thought I had discovered a little bit of egalitarianism when I reached the maid’s room: it was also covered in Morris paper (willow). “How nice,” I thought. Pah! The room was papered in the twentieth century; the maid would have had plain painted walls. (Which might have been a relief for her to retire to each night after so much pattern during the day, admittedly.)

And then, heading to Holland Park Road and Melbury Road, I discovered the Design Museum (formerly the Commonwealth Institute). It’s an astonishing building because of its roof, but – according to the Twentieth Century Society – it was an even more astonishing building when it opened in 1962. I found its exhibits a bit underwhelming: examples of good design were those that have been around my whole life or I have seen (and been intrigued by) before. There’s a limit to how many times I can be stopped in my tracks by the Frankfurt Kitchen or an anglepoise lamp, brilliant as they are. At least they are on display to be discovered for the first time by young people – although it’s very ageing to see commonplace artefacts from one’s life presented in an historical context!

And finally to the “Holland Park Circle” – houses of Victorian artists clustered around Lord Leighton’s House. They were all very fine and surrounded by gardens, but the only one that I really liked was at 8 Melbury Road – built 1875-77 by Richard Norman Shaw for Marcus Stone. All that light – such a contrast to Sambourne’s house! I was ridiculously pleased to discover that Michael Powell lived there from 1951-71. The other notable house was designed for himself by William Burges – whose hideous painted furniture I had seen yesterday in the V&A. I realised that he had also designed St Mary’s at Studley Royal.

Afterwards, I looked at what Nairn had to say. I loved his description of Leighton’s house: (“the nominal architect Aitchison seems to have been brought in to ensure the decoration didn’t fall down”) but he disliked my favourite, finding it full of “surface tricks”. Not for the first time, I have little idea what Nairn means.