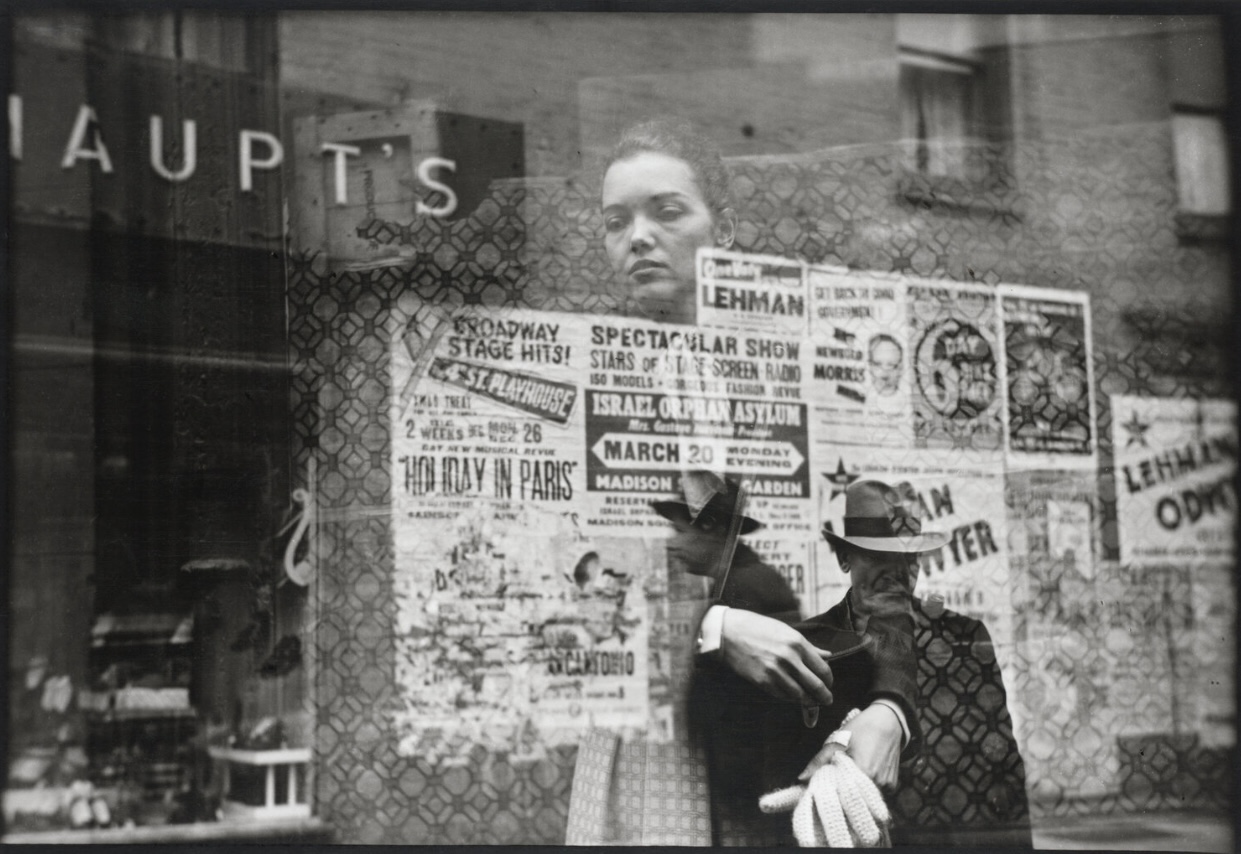

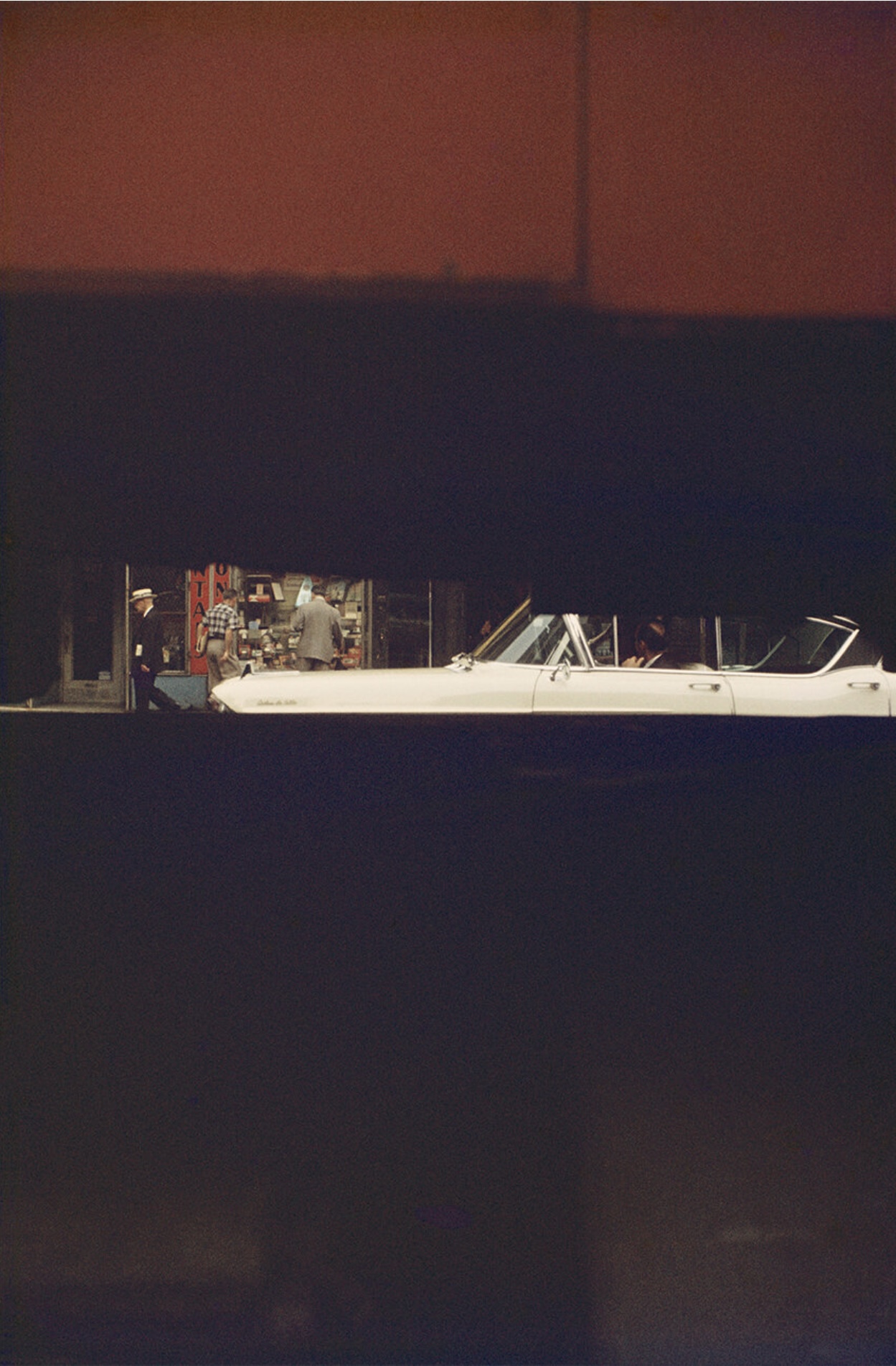

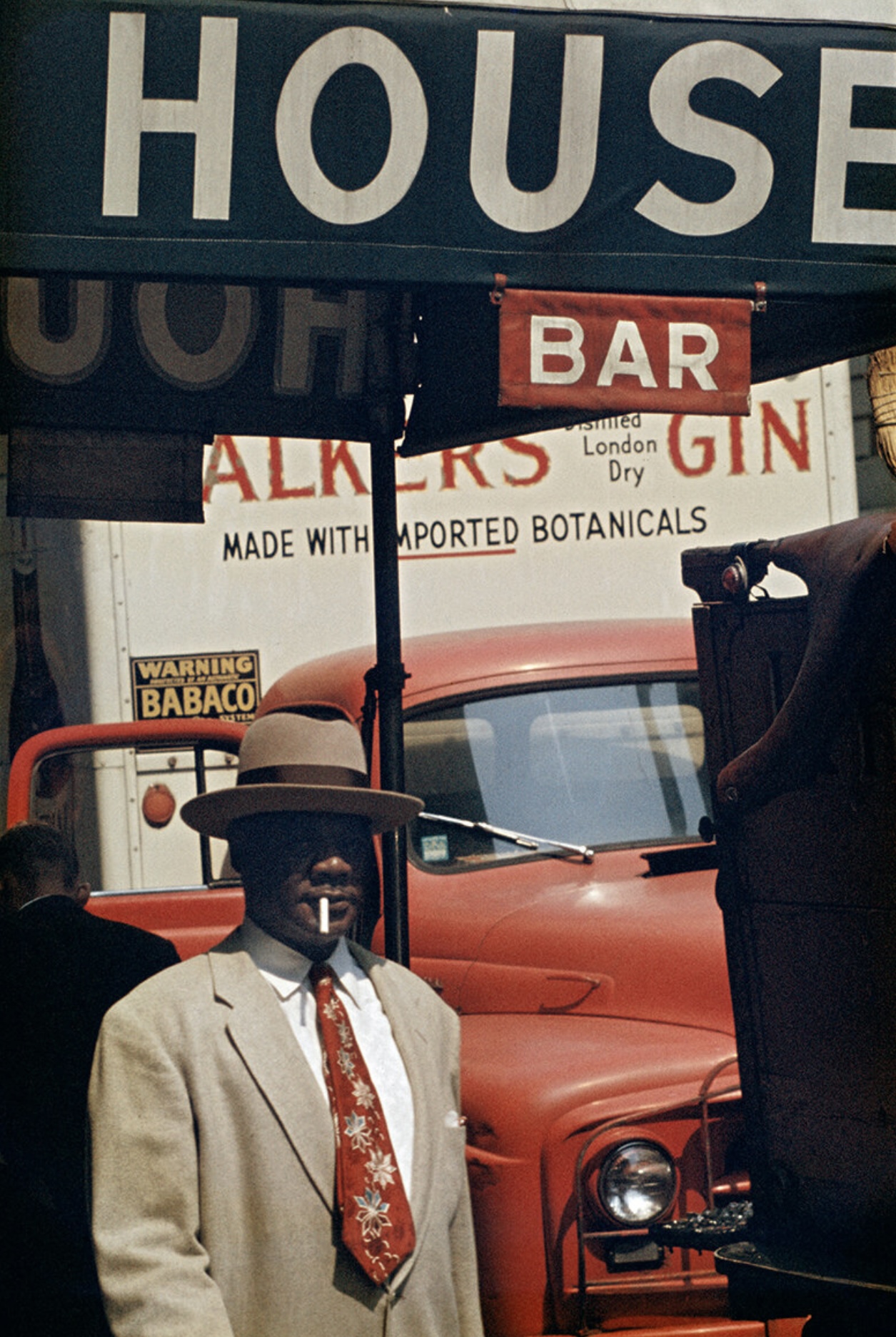

I came to Milton Keynes to visit an exhibition of photographs by Vivian Maier – mostly taken in 1950s, 60s and 70s New York and Chicago. The passage of time and changes since then made for a fascinating exhibition: wonderful B&W square prints and then the sudden jolt to rectangular colour prints where Maier used colour almost as the subject, and finally to some very shaky film. Each print in the exhibition cried out to be looked at carefully – whether it was in the composition, capturing a moment, the hint of a story or the technical brilliance. I wrote down several adjectives as I wandered around: witty, abstract, tender, detached, unflinching, driven, nosy. Maier was taken with reflections, formal composition and juxtapositions. (I like the LIFE headline below the dozing newspaper seller.) It must have taken some nerve (in both senses) to photograph some of her subjects: some look as if they’re about to tell her to get lost.

With children, she was brilliant: they are natural as they look at her camera. Portraits of wealthier people are taken from behind or at an angle, as if she had to catch them unawares, whereas it looks as if ordinary people were willing to be addressed by and pose for her. She also photographed those who were down on their luck. Her gaze doesn’t waver here: she documents the hardship, even though the photographs were never seen. There seemed something pitiless in her gaze until I read that she was outspokenly liberal, which changed my view of her.

Maier earned her living as a live-in nanny or carer, and she seems to have been alone in the world from an early age. One senses this in the self-portraits: a kind of proclamation that says “I exist and this is my proof”. She sounds eccentric, secretive and even obsessive: she left over 100,000 negatives but rarely showed her photographs to anyone. But, my goodness, what an eye she had and what single-minded purpose she showed. I can’t pick out a favourite: I loved the abstraction of the bed springs and the torn netting, but equally the tenderness of the linked hands and the little girl holding onto her mother’s skirts moved me. In a more detached frame of mind, I would pick out the woman walking alone under the stoa: a single human figure dwarfed and duplicated by monumental architecture.

After lunch (on the fourteenth floor: I rise and rise), I cycled to Bletchley for a nostalgic visit. Each time I find myself further from my moorings: once these were streets of working-class family houses, but now they are inhabited by working-age adults who turn gardens into car parks and lean-tos into living spaces. The only trace I could find in my parents’ old house were some Japanese anemones. Almost twenty years ago I planted some from my own garden into their front garden and they thrived. I will assume that these are the very same flowers, since nothing about the house now suggests that the residents tend to anything other than their own business.